The story of Dick Whittington featuring many London landmarks all with their own stories

Bow Bells

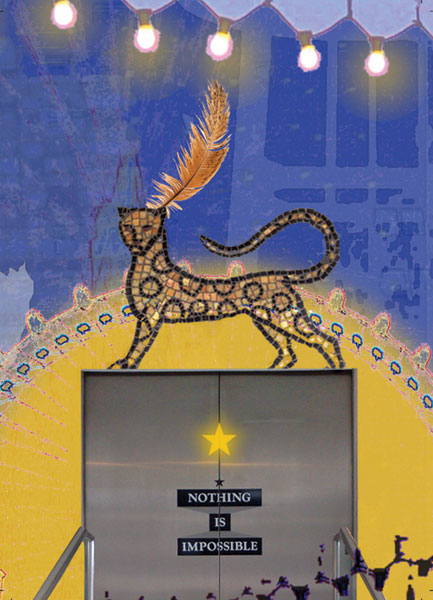

Peter Jones #SloaneSquare – Leopard with a feather in his cap

#LondonEye

NationalTheatre with Anthony Gormley figure on roof

Cat grafitti from London park bench

Gaz’s Rockin blues #RadioFutura

Ladbroke Grove #Gasworks.

Royal crowned #RegentsPark signposts

Lights on the Embankment….

many thanks to Clare Gibson for further stories of the mosaic

http://mrssymbols.blogspot.com/2010/04/hidden-life-of-peter-jones-mosaic.html

“A symbolic reading of the mosaic

At first sight, the mosaic appears to depict a conventional enough symbolic scene: a tree of life, harbouring an owl, guarded by a pair of animal protectors, soaring above the words ‘PETER JONES’, the shop’s name being set amid undulating waves and flanked by two hippocampi and a couple of starfish. The clean, sans-serif lines spelling out the name, along with the Art Deco elegance of the big cats and starfishes, complement the Modernist style of the building’s King’s Road façade, suggesting that this fundamentally ancient, archetypal image was adapted to suit a between-the-wars taste. Something niggled, though. Although birds, animals and marine creatures are commonly used to represent the sky, earth and sea in artistic convention, the single owl (rather than, for instance, a pair of peacocks) and choice of lynxes or leopards (instead of, perhaps, deer facing one another) seemed odd in the context of a traditional, sacred-tree scene rooted in the art of ancient Mesopotamia. And why choose such a scene to welcome customers into a shop, of all places? So I resolved to investigate it further and snatched a quick photograph before heading home.

I was satisfied that most of the mosaic’s symbolic components were appropriate for a fertility-celebrating, tree-of-life image: the starfish and fanciful hippocampi represent thriving marine life; the aquamarine waves, the waters of life; the rich brown earth, the life-giving potential of the soil; and the tree’s green foliage, flourishing vegetal life. The big cats remained something of a puzzle, though, as did the owl, for none are conventional motifs in this context. That said, lynxes can signify keen-eyed watchfulness, while leopards were sacred to the Graeco–Roman fertility god Dionysus/Bacchus, and the owl, to Athena/Minerva, goddess of wisdom (so maybe the tessellated tree denoted the tree of knowledge rather than of life), all allusions that could conceivably explain these creatures’ inclusion in the mosaic.

‘Coloured marble mosaic in an amusing pattern’

Still curious, I contacted the John Lewis Partnership’s Archives Department to ask if it held any information on the Peter Jones mosaic, and received a helpful reply. It seemed that there was little documented information on the mosaic (which was noted as being ‘An interesting exotic mosaic on pavement incongruous with new building’), whose date of creation was pinpointed to 1932–33, when the Cadogan Gardens part of Peter Jones – the elevation directly above the mosaic – was built as a prototype by the architects J A Slater and A H Moberley and their associate, William Crabtree. Indeed, an article entitled ‘Current Architecture’, by J R Leathart, which appeared in the May 1935 issue of Building, referred to the entry to Peter Jones’ new extension at the back of its Sloane Square premises being ‘covered with coloured marble mosaic in an amusing pattern’.

William Crabtree had, in fact, been working for the John Lewis Partnership as an architectural research assistant since 1930, having been introduced to John Spedan Lewis – who is known as ‘the Founder’ within the John Lewis Partnership – by Charles H Reilly, a professor at the University of Liverpool School of Architecture, from which Crabtree had graduated. Spedan was the son of John Lewis, who was already the founder–owner of the John Lewis department store on Oxford Street when he bought the Peter Jones department store in 1905. In 1914, his father transferred responsibility for Peter Jones to the 29-year-old Spedan, a visionary thinker who went on to transform the family business inside and out (not least by establishing a profit-sharing partnership for employees during the 1920s). Crabtree’s brief was to research the proposed rebuilding of Peter Jones, and it was his design – created with consultant architect Reilly and resident architects Slater & Moberley – that was approved for the new building based on the experimental prototype. On its completion in 1939, the remodelled department store extended on its island site along the King’s Road to Sloane Square, its famous glass curtain wall – influenced by the work of German architect Erich Mendelsohn and the first in Britain – then curving around the Sloane Square end to Symons Street.

Today classified as a Grade II* listed building, Peter Jones recently underwent an extensive, award-winning renovation by architects John McAslan + Partners that is as notable for its sensitive retention of historical features as for its modernising programme. Stand in Cadogan Gardens facing the mosaic, and you’ll see that the part of the building into which it leads is bounded to the right by Crabtree’s streamlined International Modern vision (this section, the former 29 Cadogan Gardens, dates, in fact, from 1964) and, on the left, by an Arts and Crafts studio house dating from the 1890s. This is 25 Cadogan Gardens, which was designed by A H Mackmurdo for the artist Mortimer Menpes. Turn the corner, and the red-brick section that you’ll see fronting Symons Street is a remnant of the building that was completed for draper Peter Rees Jones in 1895 to house his eponymous department store.

John Spedan Lewis: ‘first and foremost a naturalist’

It was also – crucially – reported from the John Lewis Partnership Archive Collection that the images within the mosaic reflected John Spedan Lewis’ love of natural history. He is celebrated today as the instigator of the John Lewis Partnership’s successful profit-sharing, mutualist model, but Spedan chose to describe himself as ‘first and foremost a naturalist’. No dabbler in natural sciences he, Spedan was vice president of the Zoological Society of London from 1939 until his death, his special interests being horticulture, ornithology and entomology (fields that the John Spedan Lewis Foundation continues to support).

On delving a little deeper into Spedan’s decidedly hands-on interest in the natural sciences, I was delighted to learn that he kept owls at his country house in Wargrave, Berkshire, during the 1920s, and a pair of lynxes in outdoor cages at North Hall, his north London home. And with that, the final pieces of the tessellated puzzle fell into place.”